For many years, Moss Kendrix was the host of a weekly radio program "Profiles of Our Times, " on WWDC .

Moss Kendrix was a public relations pioneer who left a lasting legacy and a major imprint on the way African Americans are portrayed through the power of advertising. During his lifetime, he designed countless public relations and advertising campaigns that promoted African-American visibility for news organizations, entertainers, and corporate clients including Carnation, the Ford Motor Company, and the Coca-Cola company.

He educated his corporate clients about the buying power of the African-American consumer, and helped to make America realize that African Americans were more complex than the derogatory images depicted in the advertising of the past.

A brief bio

Born in Atlanta, Georgia in 1917, Kendrix's early education was obtained through the local public schools, and he counted future entertainer Lena Horne as one of his close childhood friends. He later attended Atlanta's Morehouse College, a respected college for African-American men.

Kendrix was a popular college student, who became the editor of the Morehouse newspaper The Maroon Tiger, and a member of Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity. He was also the co-founder of the Phi Delta Delta Journalism Society, the first and only society of its kind for African-American journalism students. In 1939, just after graduating from Morehouse, Kendrix created National Negro Newspaper Week. He was accepted into Howard University's Law School in 1939, but opted to gain work experience. That same year, he married Dorothy Marie Johnson, a student at Spellman College, the sister school to Morehouse. They had two sons, Moss Kendrix, Jr. and Alan Kendrix.

Drafted in 1941, Kendrix served in the United States Army. During that period he worked for the Treasury Department in the War Finance Office and traveled across the country with African American celebrities promoting war bonds, and often appeared on radio shows for the CBS network. Two of his favorite celebrity spokespersons were composer/musician Duke Ellington and singer Billy Eckstine.

In 1944, Moss Kendrix became the director of public relations for the Republic of Liberia's Centennial Celebration, and his successful work for this event is believed to have been the inspiration for his future career in public relations.

That same year, he founded his own public relations firm, The Moss Kendrix Organization. The company motto, “What the Public Thinks Counts!” was also his mantra, which he embossed on the organization's letterhead. Based in Washington, D.C., the organization was in charge of major accounts targeting African-American consumers. The Coca-Cola Company, Carnation, the National Dental Association, the National Educational Association, the Republic of Liberia, and Ford Motor Company were all clients of the firm. In addition to his corporate work, Moss was also the host of a weekly radio program, "Profiles of Our Times," on WWDC for many years.

The Moss Kendrix Organization gradually phased out of operation in the 1970s, but the legacy of his work continues to live on. Moss Kendrix died in December, 1989.

The Legacy of Moss Kendrix

The impact that Moss Kendrix left on the world of advertising can be seen everywhere. Billboards, magazine advertisements, television commercials, and radio ads routinely use positive images African-American actors, models, and voice over artists to sell products.

Without the initiative of Moss Kendrix and others in his field, African-Americans, Asians, Hispanics, Native-Americans and other minorities would not be represented as fully in print ads, on television, or in the movies. Kendrix made corporate America aware of the buying power of African-Americans, as well as the need to tap this powerful market for employment opportunities. This, in turn, opened up the arena for other minorities.

Improvements in the portrayal of minorities continue to occur every day. Today, the legacy of Moss Kendrix lives on in the National Association of Market Developers and other professional groups he helped to create, and in the goals and successes of African-Americans in the field of public relations.

The Coca-Cola Years

As ubiquitous as Coca-Cola is in today's culture, it has not always been a very popular drink for African-Americans. In African-American communities throughout the south during the 1920s and 1930s, Nehi's grape- and orange-flavored beverages were by far the favored product. Nehi recognized the value of the minority rnarket, while the Coca-Cola company did not. Nehi products were well stocked in the smaller African-American markets and gained a product recognition that Coca-Cola did not enjoy.

Moss Kendrix recognized this gap, and decided to act on the knowledge. In the early 1950s he went to the company offices of Coca-Cola in Atlanta, Georgia, where he made a pitch and delivered a proposal on how to market to the African-American community. He was hired by Coca-Cola and worked for them on retainer. By taking this bold action, Moss Kendrix became the first African-American to acquire a major corporate account. Moss Kendrix continued to work for the company until the early 1970s.

While Moss Kendrix worked for Coca-Cola, he became an integral part of the product promotion efforts, and he had an opportunity to work with celebrities from the sports and entertainment industries. He also had the opportunity to design promotional ads for the beverage. The pictures on this panel showcase some of the celebrities who worked with Coca-Cola, the publicity shots for the product staged by Kendrix, and human interest photographs used by Coca-Cola to promote their product.

The Coca-Cola Proposal

Fourteen million people comprise the Negro market of the United States. These people constitute a very important consumer outlet which is best cultivated by promotions and sales schemes that are psychologically angled toward the people of this consumer group.

The proposed Jackie Robinson Coke Clubs and Good Citizenship Corps, as conceived by the author of this prospectus, would embrace three projects:

A Jackie Robinson Bat Boy and Girl Good Citizenship Corps

A "Who Are America's Twelve Leading Negro Citizens" Contest

Coca-Cola Scholarship Contest for High School Seniors.

Although specifically directed toward the Negro youths of the nation, this proposal entails a plan which would indirectly reach the entire Negro population and would employ programs of advertising, public relations and sales promotion.

Advertising In the promotion of this plan, the Negro press, newspapers and magazines, would be utilized as primary advertising media. Placards, posters and other types of advertising instrumentalities would be used as conditions might warrant. In accord with the advertising policies of The Coca-Cola Company, local bottlers of Coca-Cola would cooperate in the promotion of any advertising campaign entailed in this project.

Public Relations In order to assure the successful promotion of this plan, programs of public relations would be projected to run concurrently with other phases of the project. Of necessity, such public relations programs would be of a nature to direct attention toward the project and assure best results in the venture.

Sales Promotions The sale of Coca-Cola would form the basis of participation in The Jackie Robinson Coke Clubs and Good Citizenship Corps program. Stipulations covering this participation would involve methods of marketing and, therefore, must be planned in accord with such policies of The Coca-Cola Company. Such methods would have to be organized under the direction of designated officials of The Coca-Cola Company.

THE PLAN

This plan is built around the current popularity of Jackie Robinson, Brooklyn Dodger first baseman and the first Negro to enter modern organized baseball. In addition to capitalizing on the popularity of this great athlete, the project is designed to give impetus to the Attorney General's program for the prevention and control of juvenile delinquency, and might be promoted in cooperation with the committee which has been created by Presidential approval to handle this Department of Justice youth program.

The name, Jackie Robinson, is one known and highly praised by Negro youths throughout the nation. Noting his interest in the welfare of the youths of the nation, Robinson recently accepted the leading role in a Herald Studio motion picture entitled "Courage", a film treating juvenile delinquency. Reliable sources have indicated that Robinson will donate his remuneration for appearance in this film to organizations devoted to work among boys and girls.

In 1947, Robinson was recipient of several honors in testimony to his athletic ability and good sportsmanship. He was named baseball's "rookie of the year" and, in a nationwide poll, he was voted second among the ten most popular personalities of the nation. He was listed second to Bing Crosby and above such persons as Frank Sinatra and Generals Eisenhower and MacArthur.

This is the man around whom this project would be built.

The Jackie Robinson Bat Boy and Girl Good Citizenship Corps

For boys and girls fourteen years of age and under, it is proposed that The Coca-Cola Company sponsor A Jackie Robinson Bat Boy and Girl Good Citizenship Corps.

Boys and girls in the above age group would qualify as members of the Corps by submitting brief good citizenship slogans. Under any condition, each boy or girl having submitted a slogan would be given an attractive good citizenship certificate and a button.

Both the certificate and button would carry the likeness of Robinson. The certificate, signed by Robinson, would carry the great athlete's "do's and don'ts" of good citizenship and a seal crediting The Coca-Cola Company for the sponsorship of the project.

Many boys and girls would frame their certificates and would keep them throughout life in honor and memory of Robinson. Coca-Cola would profit through the creation of present and future markets. Parents would be greatly impressed by such a worthwhile venture on the part of The Coca-Cola Company.

For best results at the "Coke" counters, this project should be launched in the summer and may extend for an indefinite period of time.

Jackie Robinson Asks, "Who Are America's Twelve Leading Negro Citizens? Why?

"Who are America's twelve leading Negro citizens?''... Jackie Robinson asks the question ... Negro boys and girls between the ages of fourteen and eighteen answer through The Coca-Cola Leading Negro Citizens' Contest.

This contest would extend over a period of six weeks commencing about October 1st and extending until about the middle of November. The twelve leading citizens would be selected from brief essays written by boys and girls within the age range stated above. (Note suggested ad copy at close of this section.) Educational leaders, schools, YMCAs, YWCAs and other social agencies working with youths would be asked to cooperate in this project.

Selection of the twelve leading citizens would be made upon the basis of the number of essays received devoted to a given individual, with each essay counting as one vote. The girl or boy submitting tile essay judged best in each winning group would be given a modest but worthwhile award. (Please note ad copy).

A panel of Contest Judges would select the winning essays during the period between the close of the contest (mid-November, and the 20th of December. Persons having been selected among the twelve leading citizens would be announced in full page advertisements of an institutional nature carried by The Coca-Cola Company and its bottlers during the first twelve weeks of the year following tile close of the contest. Appropriate advertising and public relations would be employed prior to and during the six-week period of the contest.

No persons other than contest officials, judges and interested officials of The Coca-Cola Company would know the identity of persons having been selected "leading citizens" prior to the week during which the individual is featured. Such a procedure would stimulate tremendous interest within the Negro population of the nation.

Jackie Robinson asks:

Who are America's 12 Leading Negro Citizens?

Who? (Brief biographical sketch of leading citizen of the week, chosen from contest entries.)

Why? -- Leading Citizen's message to youth?

Winning essay on leading citizen of the week.

"These Twelve" Scholarship Contest

At the outset of the running of the institutional advertisement series featuring the selection of America's twelve leading Negro citizens, it is proposed that The Coca-Cola Company announce a scholarship contest to be known as "These Twelve Leading Citizens."

This contest would be open to high school seniors only who would compete by writing lengthy essays (number of words to be later decided) devoted to the twelve leading citizens. Four 41,000 scholarships might be given on a regional basis, or under other conditions, which would permit local bottlers to cooperate in the venture. Regulations in keeping with good scholarship, etc. would be later worked out.

Cooperating Interest

In each of the above introduced projects, Jackie Robinson would be used where possible to boost the participation, interest on the part of Negro boys and girls of the nation. Civic, social, fraternal and professional organizations would be requested to aid in the promotion of this project, which would have as its primary objective the forwarding of good citizenship among Negro boys and girls.

It might be wise if no direct sales promotion were attached to this plan, but handled locally by bottlers independently of the national projects.

THE PROFITS

In that the sponsorship of this project would represent a significant contribution to the general welfare of the nation, its profits to the Coca-Cola Company and its bottlers would be immeasurable.

Direct profits to be acknowledged by Coca-Cola would be tremendous and far-reaching. In addition to capitalizing on the current Negro market, the project would embrace a type of public relations involving youth which should tend to cultivate future markets. The Coca-Cola Company, in displaying interest in the children of the present Negro market, should note a type of appreciation on the part of Negro parents that would definitely pay dividends in increased sales of "Coke."

Many of the persons who would be selected among the twelve leading Negro citizens are outstanding personalities in various fields of national endeavor, heads of national organizations, etc. In essence, these persons would endorse Coca-Cola -- and their "publics" would doubtless represent significant segments of the Negro market. Coca-Cola's already vast popularity at social gatherings, sporting events, at the "coke" counters, and in the home would be further enhanced through the Company's sponsorship of this project.

Since favorable publicity would of necessity result from a venture of this sort on the part of a manufacturer, it would be expected that The Coca-Cola Company and its bottlers would receive enormous coverage in the Negro press.

The National Association of Market Developers (NAMD)

While Moss Kendrix worked for Coca Cola, he became an integral part of the product promotion efforts and had the opportunity to work with celebrities from the sports and entertainment industries such as The National Association of Market Developers

The National Association of Market Developers (NAMD) was launched in 1953 at Tennessee State University by Moss Kendrix. According to Moss Kendrix, Jr., the association was viewed by his father as a support group for minorities in the public relations field. The association is still in operation today.

In 1954, the NAMD was incorporated in the District of Columbia by Kendrix, Wendell P. Alston, Esso Standard Oil Company, Alvin J. Talley, H. Naylor Fitzhugh, Howard University Marketing Professor, an associate of the Moss Kendrix Organization who became vice president of PepsiCo, and Raymond S. Scruggs, American Telephone and Telegraph Company.

In 1978, at the NAMD’s silver anniversary conference, Moss Kendrix was honored as the group’s founder and named President Emeritus. In 1980, he was again honored at a NAMD reception on his 63rd birthday during which birthday wishes were received from President and Mrs. Carter.

Special Report: The changing face of the urban markets

This report appeared in a 1962 issue of Food Business

Negroes are emerging as a major segment in the total city scene — in the big food dollar markets. They spend heavily on national brands, rarely private label.

The outstanding fact about the Negro market today is its emergence from the very framework of a "minority market" and its rapid development as a major economic force in the major cities of the U.S. This is happening through a sort of economic gerrymandering process whereby Negroes, who make up 10.5% of the U.S. population, are concentrating in the big cities — where this percentage is more than doubled: Negroes today comprise more than 25% of the aggregate population of 78 major cities — primary markets where about 2/3 of all retail sales are made and where most sales efforts are concentrated.

A more-than-25% slice of 78 major markets of the country hardly qualifies as a "minority." It's enough to make or break most sales efforts. For food marketers, the growing urban Negro market segment offers special enticements:

Negroes spend up to 12% more at supermarkets than do whites. Negroes are acutely quality-conscious, national brand-conscious.

Negroes offer a largely untapped market for many specialty foods.

egroes spend heavily on convenience foods — the generally higher-profit items.

A STAFF REPORT

Location of the Negro market in 1962 is the big reason why this market is taking on a new significance. It isn't a primarily southern market anymore. The 1960 census shows that slightly more than half of the nation's 19 million Negroes live outside the old south (the 11 Confederate states) and more are moving out all along.

But it's not just a migration northward; it's a migration to the big cities all over the country. More than half of all Negroes live in 78 cities — more than 1/3 the total live in the 25 biggest cities alone. The effect of this concentration has been enormous — Cleveland, 28.6% Negro; Chicago, 22.9% Negro; Houston, 22.9% Negro; Philadelphia, 26.4% Negro; Washington, D.C., 59.3% Negro.

But what exists today is only half the drama. The other half comes when present migratory trends have more time to develop. Professor Donald J. Bogue, population expert at the university of Chicago, forecasts that by 1975 — a scant 13 years from now — Chicago, now 22.9% Negro, will be more than 50% Negro. And there are a number of cities — New Orleans, Detroit, Cleveland, Atlanta, Memphis, St. Louis, Philadelphia — that have a higher percentage of Negroes today than Chicago does and could theoretically become primarily Negro sooner.

How fast this population change can work shows up in figure for Washington, D.C. In 1950, the city was 34.5% Negro. In 1955 it was 42.5%. By 1960 it was 53.9%.

But percentage figures alone don't tell the whole story. New York City for example, is only 14% Negro today. Yet the Negro population of New York City — more than 1 million — is more than equal to the sixth largest city in the country.

Obviously, what has occurred is that urban white populations have moved in droves to the suburbs and Negroes are taking up the void in the cities. But not so obvious is the resulting paradox in food marketing strategy in the big cities: Food marketers still approach the big cities with sales appeals that are almost entirely directed, at least subconsciously, to white population — while the population itself is becoming less white, more Negro. The result is badly misdirected that may explain some of the chronic profit griefs food marketers complain of. Downtown department stores long ago perceived the Negro's role in the profit picture. To date, relatively few food marketers have.

Purchasing power of the Negro market is what makes the market's geography so important. The Negro's annual dollar spending is currently pegged at about $20 billion — roughly equal to the entire purchasing power of Canada. Of this, Negroes spend nearly 20% ($3.75 billion) in food stores. (The population as a whole also spends about 20% on food, but this includes spending in restaurants where Negroes spend very little.) There are several statistical reasons why the Negro is an exceptionally important food store customer (see chart, "Commodity Negro purchases in excess of white"):

the Negro housewife is shopping for more people (average Negro family size is 4.4 people; average white: 3.6), and

he's spending from 2% to 12% more on food than the white housewife.

Reasons for this extra spending on food include the fact that 50% more Negro wives work than white wives, plus the fact that social barriers prevent the Negro from spending much at restaurants, on homes, in travel, etc., where whites can and do spend freely. The point is, the extra money Negroes spend on food is a relatively stable factor for food marketers to consider. Beyond this point, national statistics become less important — if not downright misleading to food and beverage marketers. A classic instance: Among whites, the primary market for scotch is in the $8,000-and-above income group. The median income for Negro families is only about 50% of the white family median, so scotch would seem to find only a small market among Negroes. But as a matter of fact, it is estimated that Negroes buy about 40% of all the scotch consumed in the U.S.

Even that national figure of family median incomes at 50% of whites obscures the fact that Negro family incomes average about 80% of white family incomes in such key markets as Chicago, Detroit, Los Angeles, New York, Washington and San Francisco. (There are, incidentally, a few towns — Saginaw, Mich., and Johnstown, Pa. — where Negro median income is reported to be higher the white family income.)

The lesson here is that white income-consumption relationships can't be applied to the Negro market. Neither can national statistics about Negroes offer any real guide to local markets where market potentials have to be measured and sales efforts made. The Negro market requires evaluations for each local market being considered. This is particularly true of food.

What Negroes buy in the way of food and beverages varies from white preferences in several significant ways. "Where many food marketers and grocery retailers are losing business from the Negro," Ebony publisher John H. Johnson told Food Business, "is in adjusting the stocks of grocery stores in the neighborhoods that have become, or are becoming, primarily Negro neighborhoods. This change means different customers with different tastes to be satisfied." Johnson estimates that as much as 10% of a supermarket's shelf space would be affected by a proper reallocation.

The differences in stock would be in five areas:

Increases in foods that Negroes consume more of than whites.

Additions of specialty foods not normally carried by stores retailing to northern whites.

Increases in the percentage of shelf space devoted to quality products and national brands -- with a consequent decrease in private label allocations.

Increases in the large economy sizes of items Negroes buy heavily in.

Decrease of space for items Negroes consume less of than whites.

Exactly what food items are involved? Here is an alphabetical list of some food store commodities and the percentages by which Negro percentages of them exceeded white purchases, based on a study in Memphis in the last half of 1960.

Fresh meats and poultry, key items in most food stores, are also areas of major variation between white and Negro preferences. According to Department of Agriculture consumption figures, the Negro household consumes 3% more meat of all descriptions by weight than the white family, 6% more chicken and turkey by weight. The most important single meat: pork. Negroes eat 3.5% more pork by weight than all whites. Bread is another key staple which Negroes eat more of, about 15% more.

Convenience foods are important, largely owing to the greater percentage of Negro wives who work than white wives. Negro families buy 26% more frozen vegetables than the white family, 22% more prepared flour mixes, 20% more refrigerated biscuits (a very important item on the Negro family table)

Beverage consumption by Negroes is vastly different from the white population. They use less coffee and tea than the white family. But they consume 41% of all the fruit ades sold in the U.S. Alcoholic beverages are very big in the Negro market — more than 90% of urban Negro households regularly drink or serve some kind of alcoholic beverage. Of these consuming households, 87.5% regularly serve beer, according to Johnson Publishing Co. research. Brand preferences? Heavily in favor of the big 5 national brands that have strong quality images — and strong marketing efforts aimed at Negroes.

Then there are the food specialties Negroes like that aren't normally stocked for white consumers outside of the south. Most of them are southern food preferences — hominy grits, black-eyed peas, okra, mustard greens, hamhocks, chitterlings, etc. Chitterlings (i.e., "chittlins" — smaller intestines of pigs, usually fried or boiled) are one of the delicacies many Negroes gave up when they came north, partly because there was almost no supply of them and partly many associated chitterlings with the old days they'd rather forget. But chitterling marketers have adjusted to this situation, are now promoting chitterling hors d'oeuvres in the north and winning new acceptance for the product.

A key difference between white and Negro food preferences is the Negro's special demand for the quality image and the quality product — ultimately the national brand rather than private label. Reason for this is the Negro's determination to enjoy the symbols of status wherever he can, whatever the price. According to Ebony publisher Johnson, the Negro is quicker to consider the quality image than the white. He allows the price factor to determine only the quantity bought. "If you want to epitomize what the Negro wants in food products," Johnson told Food Business, "it's the quality item out in the large economy size. The Negro market, therefore," Johnson added, "is a market for the national brands, not the private labels."

Negro brand preferences within the different commodity groups may in some cases vary considerably from white preferences, also requiring a change of emphasis in shelf space locations. A big factor here that doesn't affect the white consumer is the extent to which the different brands are merchandised specifically to the Negroes, discussed further in this report.

On the other hand, there are some commodities that are less popular among Negro families than white. Cheese is an example. According to department of Agriculture figures, Negro families consume about 30% less cheese than white families

One entire commodity group that is less important with Negroes than whites is the group of products oriented to dieting. Unlike whites, most Negroes still do a considerable amount of physical work and are consequently less plagued with the overeating problem.

Marketing to Negroes is, as most people in the business know, a fairly ticklish and demanding operation. There's no need to summarize here the social history that has produced the special demands of the Negro market, except to state the resulting fundamental of marketing to Negroes: The Negro seeks recognition, in commercial affairs as in the other areas of life. Only part of this job is conventional advertising. The other part, more important in the Negro market than usual, is in public relations. It isn't just the advertising face marketers hold up that Negroes look at. More and more, these days, it's the social recognition of publicity work that's important -- including the food marketer's own employment practices.

In this situation, advertising takes on a special function in the Negro market. It is a means of displaying recognition of the Negro

by using Negro media.

by using Negro models, or

y any other element in the message that exhibits specific concern with the Negro market.

This is actually the identification factor that applies in all advertising to some extent — but with Negroes it's infinitely more important than whites.

How much more effective is the message in a Negro medium? Daniel Starch & Staff concluded from a recent study of this that Negro readership of an ad is 40% higher when it appears in a Negro medium than it is in other print media. This advantage works for ads in the Negro media whether or not models are used at all and whether or not Negro models are used. But the obvious fact is that Negroes identify with Negro models much more that with white models and therefore the Negro model is more efficient in terms of the recognition purpose. Negro models, available in most cities of the country, are mainly used for the fast-expanding Negro point-of-purchase business and for outdoor posters — to a lesser extent for print media, which are relatively few.

The media situation in the Negro market is vastly different from the general media line-up. Radio is the largest single medium, with an estimated 600 stations throughout the country transmitting at least a large percentage of their broadcasts to Negroes, and this number is increasing at the rate of about 10% a year.

Negro Radio is now widely used by food marketers. But Pet Milk has just started something new with a 15-minute syndicated show called "Showcase," produced by Gardner Advertising in conjunction with Johnson Publications. The program, being aired 3 times a week in major markets of the country, is a variety program with subject matter of special interest to Negroes. Interviews with prominent Negroes will be a major ingredient of the show. "Showcase" is believed to be the first program of its type to be syndicated on a regular basis.

Newspapers, on the other hand, are less a factor in the Negro market than general papers are in the white market in terms of numbers. There are about 60 weekly or semi-weekly Negro newspapers throughout the country, but only two dailies — The Atlanta World and the Chicago Defender.

Ebony magazine, with a monthly circulation of 729,000, is the only major national Negro magazine and it is now used by 57 of the nation's top 100 advertisers. Ebony calculates its pass-on readership brings its total readership up to 3.5 million — better than 20% of the total Negro population.

A major reason why Ebony has become such a major force in this market is the small duplication of readership with general magazines — generally less than 2% of the combined circulations. Only 1.7% of the combined circulations of Life and Ebony are the same, according to Starch research in 1961. The same calculation between Ebony and The Saturday Evening Post gives 0.5% with Better Homes, 0.8%.

The point here is that the widespread assumption that general media reach the Negro anyway and that special campaigns to Negroes aren't necessary is a doubtful premise. Even to the extent that it is true, "reaching" with advertising directed to somebody else doesn't constitute selling. This notion that general media adequately takes care of Negroes guided American Bakeries' marketing activity until it discovered that, although Negro families eat 15% more bread than white families, the company's sales in the Negro market were poor. The company reversed itself, is now on a long-term marketing campaign aimed at reaching the Negro market with promotions, point-of-purchase, and magazines. Result: a step-up in Negro consumption of American Bakeries' products.

Advertising themes that have proven effective with Negroes reflect thee same social aspirations factor that influences Negroes in other areas. The prestige image — entertainment, leisure activities, association with quality — is of particular value, in addition to the standard image of family life.

In this connection, Johnson of Ebony says that celebrity endorsements in Negro advertising aren't necessarily as important as they once were. Most Negroes who have made the grade in entertainment and the sports world, he says, are no longer novel to Negro consumers. In addition, he says, Negroes are impatient with recognition limited only to excellence in physical prowess and entertainment capabilities. The Negro doctor, attorney, businessman, or teacher might be more effective now, Johnson says, if endorsements are being considered. Another angle Johnson pointed out: Negro celebrities are not always universally popular with Negroes. Some of them are widely disapproved of, for one reason or another. So there's an element of risk in these endorsements.

Public Relations has become an area of special importance to the Negro market. And again it's the recognition purpose that has to be served. Negroes have very strong interests in their social groups — church organizations, lodges, charity operations, athletic associations, etc., — that offer opportunities for public relations efforts.

Pet Milk, for example, which has used the Fultz quadruplets in its advertising for about 14 years, now uses them for personal appearances at such social functions. Carnation regularly runs a baby health contest directed to the Negro market. Ward Baking has retained tennis champion Althea Gibson as a community relations aide for much the same purpose. Coca-Cola underwrites Negro golf and tennis tournaments.

But Negroes these days are looking more and more behind the public relations and advertising face that food marketers represent. They are looking to the company itself — specifically its employment practices — to see how sincere the recognition of the Negro market is. Use of Negro salesmen is long since acknowledged as almost a "must" for successful marketing to Negroes. Attention is now being concentrated on other areas of company activity.

The experience of Coca-Cola in Philadelphia recently is instructive. Pepsi has marketed to Negroes for several decades and had employed more than a dozen Negro marketing executives in its home office, many more Negroes in its bottling plants. Nonetheless, Pepsi was hit by a boycott in the Philadelphia market, directed by a group of ministers who insisted that Pepsi should hire more Negroes — white collar workers and truck drivers too, not just production people. Pepsi obliged.

Identification with the Negro consumer stands out clearly in this potpourri of supermarket commodity ads that appeared in the April, 1962, Ebony. The copy themes are al most verbatim the same as appear in ads directed to whites. The only difference is the Negro models. This is not to say, however, that all advertising directed to Negroes either does or must feature Negro models. Many brand advertisers use no models at all in Negro-directed advertising.

Awareness of the importance of such employment practices is the reason why companies like Pabst Brewing runs ads in Negro media prominently featuring a Negro employee of the company.

Dixie Negroes' Buying Power; Of $3.5 Billion Stirs Business

By Joseph K. Heyman

Southeastern Business Consultant

Three and a half billion dollars a year — that's the present size of Negro buying power in the Southeast.

Businessmen throughout the region are eyeing this market with increasing interest.

Already many have found it well worth promoting.

Back in 1939 the region's Negro income barely broke the $1million mark. The 250 percent increase since prewar is all the more remarkable in view of the seven percent drop in the colored population.

Three factors explain the sharp gain in Negro income:

General rise in the regions' prosperity.

Better-than-average increase in job opportunities; Negro chances for employment fluctuate both up and down more than the economy as a whole.

Migration from low-pay farm jobs to higher pay city work.

The accompanying chart illustrates the third point. In the past decade the number of Negroes on the region's farm dropped about 33 percent while the number living in cities and towns increased 20 percent.

Changes in quality of the Negro market are equally impressive.

Prewar most Negro families could afford only the absolute essentials and a sprinkling of inexpensive luxury items.

Upward shifts in the distribution of income have expanded greatly the scope of potential Negro demand

Better housing, better clothing, household appliances and many other Items making for more pleasant living are now in the reach of a sizeable part of the Negro population.

The shift in family income is shown in the following table. The I939 and 1946 figures are from official sources and the 1949 data are estimates of the writer based on a recent Department of Commerce sample survey.

Almost one of every five colored families living in Southern cities and towns now has an income of $250 a month or more. Another one fifth enjoys monthly spending cash of $165 to $250.

Contrast this with prewar when less than one out of 50 were in the same two brackets combined.

On a per capita basis. Negro income has more than tripled — from roughly $150 in I939 to about $500 last year. Income per person in 1949 averaged $300 in the rural areas and over $600 in the urban centers.

The gap between white and Negro income remains large. White per capita in the Southeast in 1949, at $1,100, was more than double the average income of Negroes.

Income of the region's white population would doubtless be raised even more if Negro income continues to go up. Economic gain for one large group are bound to benefit the area as a whole.

Despite widespread migration to other sections of the nation, Negroes still make up some 27 percent of the region's total population.

The African-American Image in Advertising

I am an invisible man. No, I am not a spook like those who haunted Edgar Allen Poe; nor am I one of your Hollywood movie ectoplasm I am a man of substance, of flesh and bone, fiber and liquids — and I might even be said to possess a mind. Like the bodiless heads you see sometimes in circus sideshows, it is as though I have been surrounded by mirrors of hard, distorting glass. When they approach me they see only my surroundings, themselves, or figments of their imagination — indeed, everything and anything except me.

— Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man, 1952

The African American may be the only race in the world that still continuously confronted by a distorted self image in product advertisements. From the beginning of slavery in the seventeenth century, to the present day African-Americans have fought not only for their freedom but to be understood and respected for their unique and cultural contributions.

The struggle can clearly be seen in the representation of African Americans in advertising. The practice of advertising is to quickly link image and product in such a way that a lasting impression is created in the public's mind. Both in America and abroad, advertisers distorted the role and the image of African Americans, until everyone becomes confused by the picture represented.

This exhibition is created to provide an overview of some of the ways African Americans have been depicted in popular culture. The exhibition also highlights documents from the Alexandria Black History Museum's Moss Kendrix collection. Moss Kendrix was an African-American public relations executive, who changed the way Coca-Cola and Carnation products were marketed to African Americans. Moss Kendrix was not the only African American in the public relations field, but he was unique in his drive and ambition that began during his school days at Morehouse College.

While The African-American Image in Advertising is not comprehensive in its scope, it is hoped that the questions raised will produce a dialogue and a new awareness of the power of mass media and its ability to influence a cultural consciousness.

The African-American Image Abroad: Golly, It's Good!

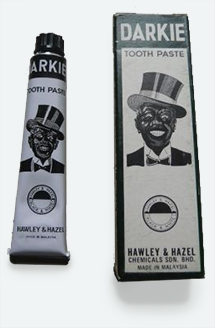

The African American visage in overseas advertisements maintains similarities to trends in the United States. Early uses of African Americans in advertisements tended to place them in servile or comical roles. While most contemporary overseas advertising follows accepted norms, a most disturbing trend is the continued use of negative images of African American males.

In Japan, "Darkie" toothpaste with its image of a wide eyed, big lipped African-American male on the box was sold as late as the 1980's. Finally complaints by Westerners resulted in a name change and the packaging being altered to reflect a contemporary African American male.

Overseas, Licorice still appears to be a product that engenders the use of racial stereotypes. Two products currently on the market, "Halva Lakritsia" from Finland and "Tabu" in Italy, both use a caricature of an African American male on their packaging. The Italian product even bases its advertising campaign on the conceit of embracing the taboo. The packaging implies that the buyer must be a daring and cutting edge consumer to even purchase a product that makes fun of a minority group.

Still the most enduring African-American image to appear in European advertising has been the Gollywog. Gollies (Golliwogg or gollys) first appear in England in the 1890's due to thc popularity of a character in Florence K. Upton's story The Adventure of Two Dutch Dolls. In the story, the Gollies are depicted as primarily male figures with a black face, wild wooly hair, wide white eyes, and large red lips. Later the Gollywog would become the trademark for the jam produced by James Robertson & Sons Preserve Company. The Golly ("wog" has been dropped from usage as it is a racial insult to those of African and Indian descent), wearing a blue topcoat with tails and bright red pants, with the slogan "Golly its good!" was used by the company through the 1980s. A whole line of golly premiums (promotional bonuses) were offered to consumers. Golly aprons, T-shirts, pins, trays, mugs cups, dolls and toast racks can be found in many European homes. In time, pressure by minority groups forced Robertson to phase out the use of the Golly. Still, the Golly remains an enduring symbol, with golly societies still active in the United States and abroad.

The Advertiser's Holy Trinity: Aunt Jemima, Rastus, and Uncle Ben

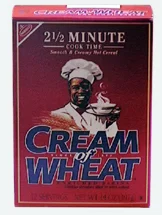

When Americans think of products advertised by African Americans, the first three that often come to mind are Aunt Jemima, Rastus (the Cream of Wheat Chef), and Uncle Ben. These faces have become American icons, representing quality and home-cooking flavor in food production. Two of the three trademark images were developed in the nineteenth century. The third image was a product of a World War II economy and all continue to be used today.

Rastus

Rastus, the Cream of Wheat chef, was created around 1890, by Emery Mapes, one of the owners of North Dakota's Diamond Milling Company. When looking for an image to adorn their company's "Middling" (Farina) breakfast porridge, Mapes, a former printer remembered the image of an African American chef used on a logo for a skillet. Using the skillet as a template, and naming the product "Cream of Wheat," the first packages were made available to the public. This logo was used until the 1920s, when the woodcut image was replaced by the face of Frank L. White, a Chicago chef who was paid five dollars to pose in a chef's hat and jacket. The face of Frank L. White has been featured on the box with only slight modifications until the present day.

Uncle Ben

Uncle Ben, whose kind face smiles out at consumers from bright orange boxes of rice, was a real person. Uncle Ben was a rice farmer from Houston, Texas whose rice crop continually won awards for its high quality. In the 1940s, Gordon L. Harwell, who later became president of Uncle Ben's Converted Rice Company was dinning in a Chicago Restaurant with his partner planning the development of this famous company, when he saw the person whose familiar face is now widely known as Uncle Ben. The men decided to name the company after Uncle Ben, after the deceased farmer whose name stood for quality. To represent Uncle Ben the men used the restaurant's maître d', Frank Brown whom they considered a good friend. For many years the picture of Mr. Brown as Uncle Ben covered the entire box of rice, but later this trademark was moved to the upper ride side of the box. Many African Americans object to the term "Uncle" (or "Aunt") when used in this context, as it was a southern form of address first used with older enslaved peoples, since they were denied use of courtesy titles.

Marilyn Kern-Foxworth, in her book Aunt Jemima, Uncle Ben and Rastus, calls Aunt Jemima "...the most battered woman in America..." which is true considering the battles fought to erase what this image meant in American culture. Aunt Jemima was created at the end of the 1880s in Missouri, when Chris L. Rutt and Charles G. Underwood invented an instant pancake flour.

Rutt created the trademark after a visit to the theater in 1889, where he saw minstrels in black face, aprons, and red bandannas performing a tune called "Old Aunt Jemima." The song, very popular in its day inspired Rutt to use the same image as the company logo. The company went through many changes through the years until it was acquired by Quaker Oats in 1926. During this time, seven women were known to have portrayed Aunt Jemima. These women made appearances at expositions, state fairs, stores, and in television commercials. The most famous of and the first Aunt Jemima was Nancy Green, a former slave. Green portrayed Aunt Jemima from 1893 until her death in 1923. Over the decades legends were written, to promote the idea that Aunt Jemima was a real cook who made the best pancakes in the south. When in reality it was a clever promotional strategy that made the company one of the most famous in the world.

Aunt Jemima

Does anybody know what ever happened to

Aunt Jemima on the pancake box?

Rumor has it that she just up and disappeared.

Well, I know the real story

you see I ran into Aunt Jemima one day.

She told me she got tired of wearing that rag wrapped around her head.

And she got tired of making pancakes and waffles for other people to

eat while she couldn't sit down at the table.

She told me that Lincoln emancipated the slaves

but she freed her own damn self.

You know

The last time I saw Aunt Jemima

She was driving a Mercedes-Benz

with a bumper sticker on the back that said

"free at last, free at last,

thank God all mighty

I am free at last."

— Sylvia Dunnavant, 1983

A Distorted Reflection: African-Americans and Beauty Products

Even when African-American companies marketed products to their own community, these early products emphasized changing one's appearance to match the accepted Caucasian norm. Straight hair was valued over kinky, and whiter skin was more prized than the varied hues that comprise the African-American race.

Advertisements for bleaching creams and hair straighteners filled the pages of African-American magazines. Opinions about hair and complexion are still " hot-button issues" for many African Americans. Movies, books, and even lawsuits have been praised, reviled and fought as African-Americans explored the options available to express their cultural heritage. More frequently than in the past, American media has made attempts to represent the wide spectrum of African-American, African and Afro-Caribbean life. Hopefully, current consumers feel at little less pressure to conform and find more freedom to experiment.

The Times They Are A-Changing 1960– 1990

The production of products and magazines targeting an African-American demographic are currently at an all-time high.

Men like Moss Kendrix were working to change the way African-Americans were portrayed in advertising as early as the 1940s and 1950s. Still, it would take the Black Power protests and riots, the deaths of civil rights leaders, and the Women's Liberation Movement to force the United States to deal with serious issues concerning race, gender, and sexuality that had been keep under the surface of American society. Advertisers were forced to acknowledge that African-Americans were intelligent consumers who would not buy products by companies that refused to represent their lifestyle in commercials and print ads. African-Americans began to vote with their pocketbooks and to actively to encourage others to "Buy Black" and support black owned businesses.

As Black History Week metamorphosed into Black History Month, many advertisers took advantage of this period to design special ads, offer premiums, and give away free "educational" materials highlighting African-American culture. Familiar promotional campaigns like Old Taylor Liquor's Great African-American Men series (with free-standing cardboard figures) and Budweiser's Great Kings of Africa poster series were among many of the promotional products available in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Soon a variety of companies and organizations including the Red Cross, Coke, Pepsi, Procter and Gamble, and Nabisco designed posters and calendars that educated, inspired, and served as public service messages. While many African-Americans were pleased with the visibility, others objected to the types of companies that were funding these materials for families. Also, objections focused on the one month out of the year "ghettoization celebration" of African-American history and culture.

While issues like Black History Month have yet to be resolved, it is undeniable that positive changes are taking place. The production of products and magazines targeting an African-American demographic are currently at an all-time high.

What the Public Thinks, Counts

from The Negro History Bulletin

By James R. Howard III

April, 1956

Moss H. Kendrix, one of the most outstanding young men in the field of public relations, continues to create new ideas in the Negro market. America's 15 million Negroes represent a rich and growing market for the things people eat, drink, wear, and use.

Their purchasing power equals that of Canada, exceeds the value of all goods the U.S. exports. In population this market is twice as big as Belgium, Greece or Australia, is 3 three times as large as Sweden. All these statistics add up to a market that can mean soaring sales for companies successfully developing the proper advertising and merchandising approaches to it.

"The vast potentialities of the Negro market" has been a theme business publications have been hammering on with consistency for the past few years. Only recently The Wall Street Journal pointed out that "sales messages must be slanted" toward the Negro people.

In the light of these facts Mr. Kendrix has exerted much of his remarkable energy and skill in an effort to get American industry keyed to the development of this relatively untapped market. He has been received in the conference rooms of several of the nation's outstanding industries, counseling businessmen on the profits they have been overlooking, while seeking new clients for his own services.

Hailed by friends and associates as "The Dreamer who works to make his dreams come true," Moss Kendrix would hasten to qualify any claims of outstanding success. Nonetheless, it cannot be gainsaid that much of the advertising, merchandising and goodwill which is exchanged between the Negro market and industry today stems from the activity and influence of Moss Kendrix in the field.

As industry slowly began to employ Negroes in sales positions, Mr. Kendrix discerned a need for a program of orientation and exchange of ideas among the members of this new sales force. He organized and has been a diligent cultivator of the National Association of Market Developers.

The purpose of this organization is to promote the professional growth and advancement of its members and thereby to increase the effectiveness of the marketing and public relations programs in which they are engaged. It seeks to "encourage and assist qualified young men and women to enter the fields of endeavor served by the members of the Association."

A Meeting with President Kennedy

Visit with President Kennedy Opens Big Weekend for Capital Press Club: Press Institute and Fictitious Female Awaradee Highlight Newsmen's Annual Event

Washington — President John F. Kennedy greeted members of the Capital Press Club at the White House last weekend when he found he couldn't attend the club's annual awards luncheon.

The President received the group of about thirty newsmen and women in the Rose Garden just outside the executive offices and was presented a gold membership card by Dolphin Thompson, the club's retiring president.

Otis N. Thompson, press club president-elect, presented honorary memberships to Pierre Salinger, White House Press Secretary, and his assistant, Andrew Hatcher. Mr. Kennedy accepted for Mr. Hatcher, who was en route to Paris.

Moss Kendrix (at right, hands clasped) was among a group of newsmen and women to meet the president in the rose garden

The annual awards luncheon was thrown into a guessing game when it was announced that "Miss Helen E. Batiste" was winner of the club's "Journalist of the Year" award. Judges made the selection of "her" work as "an outstanding job on a limited budget."

"Miss Batiste" turned out to be Ernest Goodman who has done publicity for the National Association of Colored Women's Clubs, Inc., without the knowledge of club members. Mr. Goodman is director of Information Services at Howard University.

Other Awards went for Community Relations — Mrs. Ruth B. Spencer, former member of the District Board of Education; Human Relations — Mortimer C. Lebowitz, president, Morton's Stores; Mass Communication — Miss Era Bell Thompson, editor of Ebony magazine; Civil Rights — Joseph L. Rauh, Jr., District's Democratic State Central Committee's vice-chairman.

Citations went to the Rev. James Robinson, pastor, Church of the Master, New York, and leader of Operation Crossroads Africa; Mrs. Pearlie Cox Harrison, retired society editor, Washington Afro-American;

Citizens for the Presidential Vote of D. C., a group award, and the Rev. Laurence Henry, head of the District's Non-Violent Action Group and leader of last year's sit-ins in near-by Maryland and Virginia.

At the Press Institute a panel on the subject "Africa — Challenge to Mass Media," concluded that the matter of semantics in the communication of concepts is one of the major problems confronting American mass media today.

Space limitations in newspapers, group stereotypes and the general public disinterest in most foreign affairs were also cited as problems facing the press in reporting on African as well as other foreign news.

Panelists included Alfred Friendly, managing editor, The Washington Post, Era Bell Thompson, Ebony magazine; Dr. Otto Schaler, American University, and Albert Q. Smart-Abbey, African correspondent.